roblem-solving might not be the first thing you think of when you hear “language arts,” but taking a problem-solving approach to reading and writing can be a powerful way to motivate students to want to learn.

Problem-Solving isn’t just a math thing.

Whenever we “do” language arts—in other words, any time we read, write, speak, or interpret—we are problem solving. If you’ve ever researched a car before you purchased it, or seen through a politician’s hedging, or tried to describe your symptoms to a doctor, you’ve solved a language arts problem.

Problem-solving in language arts means using language skills to understand or communicate an idea: Is this car worth the money? What’s that guy’s agenda? How can I get my doctor to understand what I’m experiencing? By some combination of reading, writing, speaking, and interpretation, you have probably solved thousands of language arts problems in your lifetime.

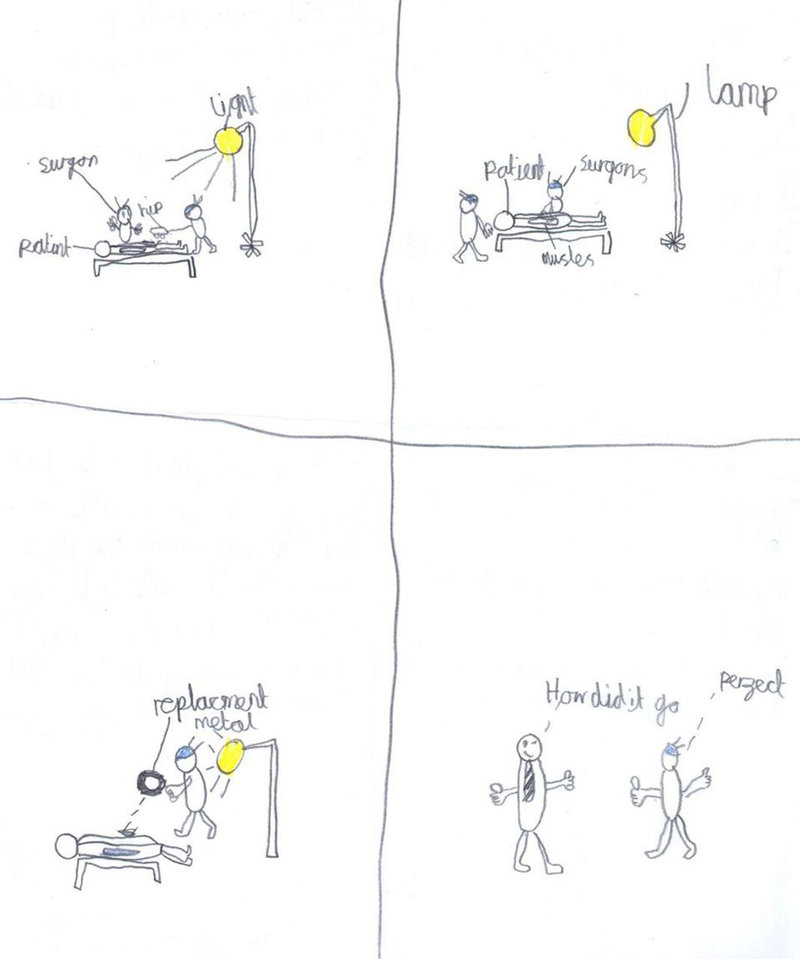

But language arts problems aren’t just personal—they can happen on a large scale, and they can impact people in very real ways. Take medical brochures, for example. In 2017, NPR reported on a problem that hospitals in the UK were experiencing. At the time, the average reading level in the UK was fourth grade, but most hospital literature was written at a twelfth-grade level. This meant that, if you needed hip-replacement surgery, your doctor was likely to hand you a brochure on par with Shakespeare or Dickens, when you were more comfortable reading Judy Blume. Granted, we tend to read at a higher level when we’re reading something that is deeply interesting to us (and what could be more interesting than your own impending surgery?), but asking patients to jump eight grade levels to understand what was going to happen to them during surgery was a problem—a language arts problem.

To find new ways of solving this problem, researchers recruited actual fourth-graders to take a crack at writing hip-replacement brochures. The students’ brochures—equal parts adorable, strange, and honest—provided a totally new perspective on what hospital literature could look like. Drawing lessons from the fourth-graders, the researchers argued for more honesty and simplicity in patient literature. In other words, the students’ writing was a small but real step toward solving a real problem.

The hospital problem crystallizes what we mean when we say “language arts problem.” For the hospitals, it was a writing problem—a need to communicate to patients in clear language, “Here’s what’s going to happen to you.” For the patients, it was a reading problem—a need to understand what was going to happen to their bodies. I love this example because it shows both sides of a language arts problem: communicating (writing) and understanding (reading).

Any time we’re trying to communicate or understand something by reading, writing, or speaking—and that’s pretty much all the time—we are solving a language arts problem.

But not all language arts problems are created equal. A good language arts problem, like a good math problem, is one that really needs to be solved. In some cases, it literally needs to be solved—patients need to understand their surgeries, you need to know whether you should buy that car or not. In other cases, a good language arts problem is just too enticing to walk away from.

Think about the last time you read a really good novel. Remember how it felt to need to read on, to not want to put the book down because you just had to know what would happen next? That’s how a good language arts problem feels.

That’s how students should experience language arts, too—and they can.

By building problem-solving into language arts curriculum, we can turn ELA subjects like reading, writing, speaking, interpretation—even grammar—into compelling problems that demand solutions.

Imagine how those fourth-graders must have felt when real researchers approached them and said, “We have these patients who really need to understand the surgeries they’re about to have, but the brochures we wrote are confusing. You’re really good at writing in a way that our patients can understand. Can you help?”

It’s hard to say no to a request like that.

That’s because the proposal doesn’t feel like an assignment—it feels like a mission. Students can clearly see the problem, they can see why they need to solve it, and there isn’t already an obvious solution. Moreover, by solving the problem, students are creating a piece of writing that people actually need. In other words, with problem-solving, students aren’t practicing reading and writing skills for the sake of practice—they’re using reading and writing skills to make something that needs to exist.

Every lesson students encounter in language arts should feel like this. The challenge is to engineer a curriculum that has problem-solving built in at every turn. This is no small task, especially when you consider the breadth of language arts education. How do you build problems that make students need to learn grammar? To master academic writing? To read nonfiction? How do you get students to really, genuinely need to think critically about information they encounter outside of school? In other words:

How do you create truly compelling problems that help students develop skills across the broad spectrum of language arts?

This is a question we’ve been grappling with as we build a language arts curriculum at AoPS. There is no formula for a really great language arts problem. (And, really, part of the fun of problem-solving is figuring out lots of creative approaches—even when the problem you’re trying to solve is how to make a good problem.) But, by working closely with students and teachers, collaborating with our math colleagues, and looking to models like the hospital problem, we have developed a few big ideas that are guiding the curriculum we’re building.

These ideas are the foundation of our Beast Academy Language Arts books, and we think they can help anyone who is interested in engineering good language arts problems for students.

1. Make it a problem, not a prompt

A prompt is an assignment: Create an informational brochure about a medical topic. Research a sea animal and write an essay that teaches readers about your animal. Write a story about a time you stood up for an idea. A student’s motivation to respond to a prompt comes mainly from outside the prompt itself. You respond to a prompt because it’s required—it’s an assignment. Some prompts are interesting or fun, and many younger students are happy to complete assignments because they want to be good students. That’s great, but it’s incidental to the prompt itself: a prompt starts from the assumption that students are going to do the assignment—it doesn’t do the work of getting students to the table.

A problem, on the other hand, starts from motivation. When you’re designing a problem, the first question you have to ask—and keep asking—is, “What makes a student want to do this?”

There are many ways to create motivation. Motivation could come from the intriguing nature of the problem itself, as with a good word puzzle or a really provocative question. Or, motivation could come from a well-crafted scenario—a writing project that’s built like a choose-your-own-adventure novel, or a grammar lesson framed as an escape room. If you’re working directly with students, you can create motivation by letting your students choose their own problems to solve, as in this compelling case study where 7th-graders took on child labor in their community and developed a range of skills—nonfiction reading, online research, analyzing and synthesizing multiple sources, public speaking, academic writing, and more—in the service of solving a problem they really cared about.

In short, creating motivation means never assuming that students will want to do something just because it’s an assignment. Good language arts problems come from a process of recognizing and rooting out this assumption at every turn.

2. Let reading, writing, grammar, and vocabulary work together.

We often think of language arts as a set of subjects, each with its own chunk of class time. In an elementary classroom, students might spend a chunk of time reading independently, another chunk doing online research for a writing project, another chunk reading nonfiction, and another chunk listening to their teacher read an authentic text like a novel or a collection of stories. Often, these separate chunks of time are devoted to separate projects: we’re researching and writing about sea animals, and then we’re reading fables; we’re learning how to read subtitles in an article about weather, and then we’re writing personal narratives. This variety can be a good thing—if you’re not jazzed about weather, at least that’s only one part of what you’re doing that day. But variety can also erase opportunities to create motivation.

Take the student who’s not interested in weather. She might be deeply invested in the other chunks of the day, but there’s little to motivate her to engage with the weather article, so she’s less likely to connect with the lesson about subtitles. What if, instead of treating it as its own chunk, we embedded the weather article in a larger problem that integrated all of the language arts chunks for that day?

Here’s how a problem like that might look in a classroom. Imagine that this is a block of about two hours in a third-grade classroom, with students transitioning between independent work, group work, and class discussion as they move through the problem. The block begins with an independent-reading warm-up, and the problem is introduced in step two:

- Independent reading (15 minutes): In this unit, we’re learning about mythology. Find a reading spot in the classroom, and continue reading the book you have chosen from our mythology and ancient history library.

- Class read-aloud (10 minutes): Gather on the rug to hear the next installment of our adventure story. Today, we find out that Zeus has gone undercover. We need to find him before he hurts someone! He’s hiding out somewhere in North America, but there’s one way to figure out where he is: as the god of lightning, he can’t help but attract unusual weather wherever he goes. Find the weird weather, and you’ll find Zeus.

- Nonfiction text practice (15 minutes): Here are two texts. One is a page from a reference book describing typical weather patterns in North America; the other is a page from a website that shows the weather in North America last week. Go back to your desk, and work with your group to compare both texts to find out where Zeus is hiding. One thing before you go: we need to work quickly to find Zeus before someone gets hurt—here’s how you can use subtitles to efficiently navigate these two texts. Okay, go!

- Share and check (10 minutes): Time’s up! Who figured out where Zeus is hiding? Which group wants to share where you think he is and explain how you figured it out?

- Writing (20 minutes): Now, you’ll work independently. Write a dispatch that will be read on the news in the area where Zeus is hiding. It’s really important to be clear in your dispatch—you’ve got to convince the people who hear it that Zeus is definitely in their region and urge them to get out, fast. If they don’t understand you or if they think you’re wrong, they might not leave, and that could be dangerous for them. Make it really clear in your first sentence that Zeus is in their region, and then give a couple more sentences to show them how you used weather patterns in the two texts you examined to figure this out. One tip: remember how we learned yesterday that “because” and “so” can help us join clauses in a sentence? Those words might be helpful tools for you. Okay, go!

- Share and check (10 minutes): Who wants to volunteer to share what they wrote? Class, imagine if you were the people this student is trying to warn. What in their dispatch would convince you that you need to heed their warning?

- Class read-aloud (15 minutes): Nice work! Come back to the rug and we’ll continue reading our class book, D’Aulaires’ Book of Norse Myths. Today we’re reading about Odin. As we read, let’s think about how Odin compares to Zeus.

When it’s integrated into a larger problem-solving activity like this, the weather text feels a lot more relevant. The problem—We need to find Zeus before someone gets hurt!—provides motivation for deciphering the weather article, and the nonfiction text feature we set out to teach (subtitles) becomes a helpful and necessary tool for solving the problem. The problem also motivates the day’s writing and grammar practice, and the whole lesson is bookended by readings that take students deeper into the world where the problem is rooted.

Put more broadly, integrating multiple language arts skills into a single problem creates motivation: it gives students a reason to need to learn each skill. We need subtitles to find Zeus quickly; we need conjunctions (“because” and “so”) to make our warning clear for the people who are in danger; we need to cite evidence to convince those people to get out of Zeus’s way. Practicing any one of these skills by itself can feel boring and unmoored from how language actually works; practicing all of them together in the context of an engaging problem makes each skill feel relevant and important.

3. Think big.

A lot goes into building a lesson like the Zeus problem. Beyond inventing the problem itself, you have to gather just the right texts for each stage of the problem. Some of those texts need to be authentic literature—for example, the independent reading at the very beginning, and the class reading at the end. You’ll also need two nonfiction texts about weather that will line up in a way that suggests where Zeus is hiding. And those two texts need to lend themselves to teaching subtitles. And they should be engaging. And one should be an online source while the other is a print source. Actually, there’s a good chance you’ll need to write those texts yourself. On top of all this, students need to have been practicing persuasive writing just before you get to this lesson, and they need to have just learned “because” and “so” so that they can apply those skills when they write their dispatches. Oh, you’ll also need to write a story that sets up the whole Zeus-is-hiding-quick-let’s-find-him scenario.

All of this may sound daunting. If you’re knee-deep in teaching your own classroom, pulling off a problem like this might actually be impossible. Building problems that knit together multiple language arts skills in engaging and meaningful ways is like assembling a ten-thousand-piece puzzle: you really need to see the whole picture before you can start putting the individual pieces together. But, with time, resources, expertise, and careful big-picture planning, a team of curriculum developers can build not just one lesson like this but entire grade levels of lessons that have problem solving built-in.

That’s exactly what AoPS’s language arts team is doing right now, as we’re creating our Beast Academy Language Arts curriculum. We are teachers, writers, and problem solvers ourselves, and—just as AoPS has done for math—we are creating the curriculum we wish we’d had when we were in school. We’ve already launched a pilot of our third-grade Beast Academy Language Arts curriculum at AoPS Academy, and we’re hard at work refining this pilot and developing our third-grade guide and practice books (including some new teachers who will be joining the faculty at Beast Academy—that’s Professor Isabella Bird, Beast Academy’s resident archaeologist and librarian, at the top of this article).

Building this curriculum is our own, rather massive language arts problem. Like any good language arts problem, it doesn’t have an obvious solution, so it will take some time for us to produce our books. But, when we do, we are confident that we are making something that really needs to exist.

Problem-solving might not be the first thing you think of when you hear “language arts,” but taking a problem-solving approach to reading and writing can be a powerful way to motivate students to want to learn.